Don’t Fear The Serpent: Australia’s Snake-Phobic Climate

Fear. We all know it, we all live with it, and it sometimes makes us act a little crazy. Fear of the dark when we’re young, not knowing what might be there. Fear of change when we get too comfortable. Fear of clowns. Hell, even fear of people we don’t know, have never met, and because of that fear, perhaps will never get to meet or understand. Fear of the unknown, fear of our own ignorance. Fear of snakes.

Why are we so afraid of snakes? As I’ve said before, I believe it’s an evolutionary response to sharing our ancestral environment with snakes. By the time our long distant relatives started leaving the trees for the savannah and the Great Rift Valley, snakes had been around for a long time, stealthily ruling the corners of a cooler, less reptile friendly, now mammal dominated planet abounding with rodents for a hungry predator. And you could include our ancestors in the “prey” category, particularly our young. No wonder there’s long been theories to explain our fear of snakes by invoking this shared ancestry and interaction. Taken to it’s conclusion, there’s even Snake Detection Theory, which proposes that not only has our brain become hard wired to recognise snakes as a defence mechanism, we have also been under selective pressure to increase our peripheral vision and general visual acuity and awareness as a response to predation pressure from snakes. This general improvement in vision and perhaps even parts of brain function could have been an important step in the development of the human mind, becoming a detail-oriented-tool-designing machine to match the master builders in the recent Lego movie.

Why are we so afraid of snakes? As I’ve said before, I believe it’s an evolutionary response to sharing our ancestral environment with snakes. By the time our long distant relatives started leaving the trees for the savannah and the Great Rift Valley, snakes had been around for a long time, stealthily ruling the corners of a cooler, less reptile friendly, now mammal dominated planet abounding with rodents for a hungry predator. And you could include our ancestors in the “prey” category, particularly our young. No wonder there’s long been theories to explain our fear of snakes by invoking this shared ancestry and interaction. Taken to it’s conclusion, there’s even Snake Detection Theory, which proposes that not only has our brain become hard wired to recognise snakes as a defence mechanism, we have also been under selective pressure to increase our peripheral vision and general visual acuity and awareness as a response to predation pressure from snakes. This general improvement in vision and perhaps even parts of brain function could have been an important step in the development of the human mind, becoming a detail-oriented-tool-designing machine to match the master builders in the recent Lego movie.

Unfortunately, some people seem to think this improvement in brain function may not be worth the billions of our kin who were munched up or “evilly murdered” by snakes throughout our shared history on this planet. Or they think such evolutionary theories are balderdash. Whatever the reason, the phrase “a good snake is a dead snake” is uncomfortably alive and well in Australia and I suspect much of the world. Of course, with the shared history of snakes and humans stacked up against us, where we have been both prey and predator alike, it seems the task of dispelling the snake-hating attitude is quite the mountain to climb. Fear is an understandable response given our two histories. Add social conditioning with perhaps a less than expected encounter with a snake in the wild to reinforce these attitudes, and the peak may seem impossible reach. But really, it’s just letting go of some baggage. Very old, crusty baggage that mostly contains mouldy underwear we no longer need, but keep for sentimental value. Because we’re human, because we’re animals with a brain, and because we’re a little crazy.

So, let’s address the phrase, “a good snake is a dead snake.” Or perhaps better, “the only good snake is a dead snake.” Mmmmm, feel the vitriol. Why? Ask anybody who speaks these words and their reasoning is something along these lines:

“Look, I love nature and all but I have the right to protect my family.”

Sounds about right doesn’t it? Fear of the snake killing a family member. Fear. And that’s ok! We are all allowed to feel fear, the fear of losing a loved one being right up there on the top of the Fear List. And so, the reptile must be disposed of with both malice and shovel. Because of fear. But here’s the statistics – we have 2-3 snakebite deaths per year in Australia, whereas insect/invertebrate bites and stings etc. cause over a dozen. Further, one of the most common ways to get bitten is to try to catch/kill the snake. Surprised? You shouldn’t be. The reason we’re getting so “dangerously” close to the the “dangerous” animal after all is because when threatened and left no option, it BECOMES a dangerous animal. And so, our fears controls our thoughts and actions, logic goes out the window, and bad things happen. Also, you can’t love nature and kill snakes. That’s hypocrisy at its finest, to say so devalues the terms “love” or “nature”, akin to removing either sausage or bun from a hot dog. Very disappointing, dear readers, and I end up biting my fingers.

Well, this is all getting quite emotional! Again, emotions may often overcome logic, case in point. Killing snakes makes me angry and I jabber like an escaped mental patient. So, let’s flip the argument and take a step back shall we? To rephrase the question without the intent of animal cruelty or the word “dead snake”, how about “what good, if any, is a live snake?” This still has that all important anti-snake sentiment we had earlier, but doesn’t cause me to shake with rage quite so vigorously. Let’s examine the utility of snakes, what we will call the “ecosystem services” they provide for us. While their aesthetic and so forth might only be appreciated by serious reptile nerds, the ecosystem services provided by snakes globally are essential for human civilization, particularly in developing countries but also right here at home. They’re an integral part of almost every ecosystem, either food or fodder, as top predators or as frequent prey, from the suburbs to the scrubs to the seas. But when it comes to snakes and humans, their main service comes down to dealing with rodents.

Humans are dependent on agriculture. It was our path from nomad-ism to settlement and the development of communities, the driver of our understanding of of the stars and the changing seasons, the genesis of cultivation and selective breeding, our first chance to really begin cataloguing the natural world around us instead of moving with seasonal resources. And we depend on grains and cereal crops today just as heavily. For example, around 90% of Queensland’s previously glorious semi-arid Brigalow Belt ecosystem has been cleared in large part for cereal cropping (that’s an argument for another day!). We’re happy to nearly annihilate complete ecosystems for grain, with further considerations usually to cattle and cotton. Throughout Asia, rice is the staple in most people’s diet, in fact throughout much of the world. With our love for grain, we have an ancient competitor. Rodents. Rats, mice, gerbils, the plethora of animals in the order Rodentia are spread across the planet, and they want our precious grains! The study of crop loss to rodents is in itself a massive field of study and of huge significance to management and economics. As such, we now know that certain months in Tanzania see up to 40.4% losses of corn (in open storage), while India experiences 2-15% economic loss through rodents across the country for all cereal and grain, and 100% losses of field crops are not a rare event! (Parshad, 1999; Mdangi, 2013;).

Enter snakes. From the predators we have available to take on the rodent problem, we have three groups to chose from. That’s birds, mammals and reptiles. I don’t imagine fish or large molluscs have a huge effect on field rats, however there may be some undiscovered catfish-thingy or some bizarre inland cthulu-type octopus which ambushes rats from creeks and drainages like a champion. And as far as amphibians, yes, I did see the YouTube video of the guy feeding the mouse to the green tree frog. And yes the giant salamander is awesome. So there are some exceptions. But also, shut up, the only paper I could find (easily, without article access from home) was from India, so no giant salamander. In India, the interface of agriculture, urbanisation and native forest means that grain loss to rodents is exacerbated. However, while active baiting and management of rats is the most targeted way to control grain loss, the snake population of India is constantly ticking away. Without snakes keeping the rat population in check, the rat plagues would reach truly epic proportions, and remember that 100% crop loss is already a reality for some. Furthermore, with such an explosion in rat populations, the vectoring of diseases becomes a concern. ‘Twas on the back of a rat, came the fleas of the black plague, I tell ye! Not to mention the other possible nasties. A survey of wild Norway rats in Maryland, USA, found over 80% carry nematode worm Capillaria hepatica, and antibodies in over 70% of rats to the Hepatitis E Virus, and over 50% for the Seoul Virus, all which are transmissible to humans (Easterbrook et al. 2007). Here in Brisbane, I wouldn’t be surprised (and have been told as much by some brilliant field ecologists!) if the majority of black rats carry, at the very least, Leptospira bacteria, a Spirochaete bacteria which can cause weeks of fever, diarrhoea, nausea, all the fun gastro symptoms plus aches and pains, with rare complications leading to death. Hooray!

This, the Ouroboros, the Uraeus, African use of snake skin talismans, and many others are the various representation of the dual handed reverence and respect given to snakes throughout the world. Only in our western enclaves have we kept the fear and lost everything else! Why are we so determined to kill snakes? Because it’s the right thing to do? No. Particularly if you’re then sharing images of yourself and your victory over an animal of probably about 1% your body weight. It’s become so acceptable to kill snakes that online images of snake killing somehow get applause and various attempts I’ve heard of reporting such blatant wildlife cruelty to the authorities always lead to nothing.

I know I’m preaching to the choir here. It’s the trap of the social media circle. Most people who I know or will read this through my contacts feel the same about snakes as I do. To us, this little article is little more than stoking the fire and stroking my ego. Fine. But to anybody who is truly snake-phobic, a snake-hater, if you’re on the fence or simply have never really given it any thought, I implore you, please, look at snakes in a rational manner. They are not evil. I’ve never heard of any wildlife professional being “chased 100 meters” by an “angry brown snake”, it only seems to happen to the average person who’s fear exacerbates the magnitude of the threat EVERY SINGLE TIME. I know you think you ran 100 meters in 5 seconds with a brown snake behind you. I also know that it was most likely a brownish but unidentified snake and you probably went into adrenaline stress phase, your vision focused in, your heart rate rising, fine motor neuron function decreasing as your organs pump blood to your central organs and to your legs, ready to fly like the goddamn wind. Because you were afraid for your life. And that’s ok! But again, let us again apply fear’s anti-venom, a fat hypodermic needle of knowledge!

What snake gives us the fear? In parts of the world it may be cobras, kraits, vipers. Let’s pick that favourite of our headlines, top of the Australian snake fatalities chart, the eastern brown snake, Pseudonaja textilis, a creature that suffers from a serious social image problem. This snake is so often mistaken to be highly aggressive. It is not, and here’s some science! In a recent study of biting behaviour in the eastern brown snake, Whitaker et al. (2000) found that almost every snake gave significant warning prior to striking with, 58% displaying the typical high standing S-bend, often with a flared neck and open mouth showing the bright pink mouth linking, and 19% by partial display with neck flared low to the ground, with 25% of bites being a complete bluff. In fact only 15% of bites were predicted to result in any envenomation, and all test were carried out under typical-hot-day-in-Australia temperatures (23 to 45 C gradient during daytime hours) to make the snakes nice and active. So much for an aggressive snake! While it may not employ the tactical headbutt as readily as, say, the red bellied black snake, 15% envenomation with 58% full display before biting and 25% completely bluffing bites doesn’t paint the same murderous villain that you may find on headlines through summer. Life and death, the cycle, and a healthy respect is all you need to climb out of the Valley of Fear and up Mount Perspective. View’s good, nah?

For the love of God, run!!

Ciao,

Janne

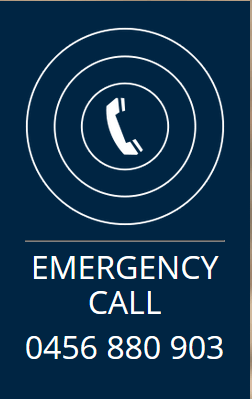

Visit Our SnakeOut Page for more information. Your SnakeOut Brisbane.

- Parshad (1999) Rodent Control in India. Integrated Pest Management Reviews. 4:2

- Mdangi et al. (2013) Assessment of rodent damage to stored maize (Zea mays L.) on smallholder farms in Tanzania. International Journal of Pest Management. 59:1

- Easterbrook et al. (2007) A survey of zoonotic pathogens carried by Norway rats in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Epidemiol Infect. 135(7):

- Whitaker et al. (2000) The defensive strike of the Eastern Brown snake, Pseudonaja textilis(Elapidae). Functional Ecology. 14, 25–31

My partner and I absolutely love your blog and find a lot of your post’s to be just what I’m looking

for. Do you offer guest writers to write content for you?

I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or elaborating on a lot

of the subjects you write related to here.

Again, awesome site!

Say, you got a nice article.Really thank you!

Howdy fantastic blog! Does running a blog similar to this require a massive amount work?

I have very little understanding of programming but I was hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyway,

should you have any ideas or techniques for new blog owners please share.

I understand this is off subject however I just had to ask.

Appreciate it!

Hi, its good post regarding media print, we all understand

media is a great source of data.

That is very interesting, You’re a very professional blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and sit up for in quest of extra of your fantastic post.

Additionally, I’ve shared your site in my social networks

I really liked your blog post. Fantastic.

Sweet blog! I found it while searching on Yahoo News.

Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News?

I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there!

Cheers

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your web site offered us with valuable information to work on. You’ve done an impressive job and our whole community will be thankful to you.